Evolution is a wonderful thing, but varicose veins are one associated aspect that humans could have happily lived without. Unfortunately, the ability to stand and walk on two legs came with unsightly and unhealthy consequences. But if you think vanity associated with the current “selfie age” triggered a deeper dislike of such visual flaws, think again. Humans have been self-conscious about their varicose veins for thousands of years. And as far as we know, treatments have been around — some more rudimentary than others — since 1550 BCE. We’re fortunate these days to have access to non-invasive medical techniques, but imagine for a moment, living centuries ago with varicose veins — what would you have done, and how would you have been treated? If you think you’re unlucky to have varicose veins, read on to understand the history of varicose veins and find out what people went through before the dawn of modern medical procedures. You might just see your plight in a different light.

Chances are, you stumbled upon this blog while researching your own venous situation. Of course, when you have a condition, it pays to know as much about it as you can, for your own peace of mind. So for a moment, let’s briefly revisit the basics: What are varicose veins? They are:

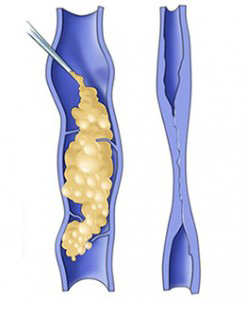

- Abnormally large, tortuous veins that typically appear in the legs;

- A cause of aching, swelling, itching, leg heaviness, and skin ulceration

So how far have humans come in the research and treatment of varicose veins? And what did people face when they needed treatment? The earliest record of varicose veins is in the papyrus of Ebers, written 1550 BCE, where the author described them as “tortuous and solid, with many knots, as if blown up by air”, and recommended people leave their veins in place.

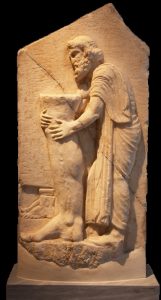

The first illustration of a varicose vein dated from 400 BCE, a votive tablet found at the base of the Acropolis — so that gives you an extra idea just how long varicose veins have been bothering people. It was around this time that Hippocrates, the “Father of Medicine”, suggested people do something about their varicose veins, because he noticed a correlation between veins and leg ulcers. This was the introduction of vein punctures, cautery (using a hot or caustic agent) and compression bandages as a treatment.

Over the next few centuries, the developments in treatments were many and varied. For example, in 270 BCE, two Egyptian physicians made surgery possible through the invention of forceps to block veins and control bleeding. But a low point in surgical history was around 0 CE, when the removal of a varicose vein was too much for even a notorious Roman warlord. He had one leg done and opted out of having the other fixed, saying “I see the cure is not worth the pain.” Today easier, more advanced varicose vein treatments are available with no down time.

Mercifully, surgical developments in varicose vein treatment continued. A Greek surgeon realized around 600 CE that the great saphenous vein — the longest vein in the human body — could be ligated or removed. Then in 1485, a landmark development was when Leonardo da Vinci produced accurate drawings of lower-limb veins, helping medical world make sense of how the venous system worked.

Two centuries after da Vinci’s drawings were rendered, the first documented attempt at sclerotherapy took place — acid is injected to create thrombus — a blood clot. This set the scene for the 1800s, where a flurry of medical developments were made. Charles Gabriel Pravaz invented his injection syringe made of glass, rubber and leather, and Francis Rynd followed up with the hypodermic needle.

By the 1900s, critical tools of the trade had been invented, and surgical processes were now being refined and published. Options included saphenous vein ligation; vein perforation to treat ulcers; and application of a special agent to close varicose veins. The links between chronic pelvic pain and vein congestion in that region were discovered, known as pelvic venous insuficiency, and Sven-Ivar Seldinger figured out a technique to access veins using guidewires.

Enter the modern age of venous treatment. Since the 1960s, treatment of vascular disease has included the use of guidewires, catheters, angioplasty and stents. If you had vascular issues these days, you were fortunate to have surgeons with many cutting-edge treatment options at their disposal. More recent and sophisticated treatments tended to have impressive scientific titles, such as duplex ultrasound scanning, radiofrequency ablation, foam sclerotherapy, and diode laser.

Which brings us to now. Do you have a vascular disorder that concerns you? Rest assured, medical development has never stopped. Perhaps your treatment might include a ClariVein device, which can be used without tumescent anesthesia. Asclera is an option for closing small veins. And VenaSeal is a system that closes veins using an adhesive agent. Your specialists know just the right treatment for you and you have nothing to worry about. The days of the painful surgery that so terrified the Roman warlord are thankfully a thing of the very distant past.